Golf Crimes

Masters treasures went missing, then the FBI showed up

The first item the young man stole from Augusta National was a green and white golf towel. This was just after the 2007 Masters, when he had come to understand it was customary for warehouse employees to take one or two small things—a hat, a flag, a shirt, a mug emblazoned with the iconic club logo—from piles designated for destruction. The 22-year-old was a college dropout whose previous job was waiting tables at nearby West Lake Country Club.

So was set into motion the most brazen thefts the game has ever known.

On March 19, 2025, Richard Brendan Globensky, an Evans, Ga., native who goes by Brendan, was sentenced to 12 months in prison. He got off light because he never wasted anyone’s time denying his guilt, voluntarily sold his house inside Champions Retreat to send a check for $1.6 million to Augusta National, and for two-and-half years energetically cooperated with the FBI to implicate other people.

Some basic facts have been known for a while. Across more than a decade of employment, Globensky regularly stole merchandise in increasing quantities. If not for also taking historical memorabilia, he might have gotten away with it. In 2022, he was arrested shortly after Arnold Palmer’s 1958 green jacket from his first Masters win was seized outside the Lincoln Park, Chicago home of a reputable collector who had been confident of the item’s honest origin until that moment.

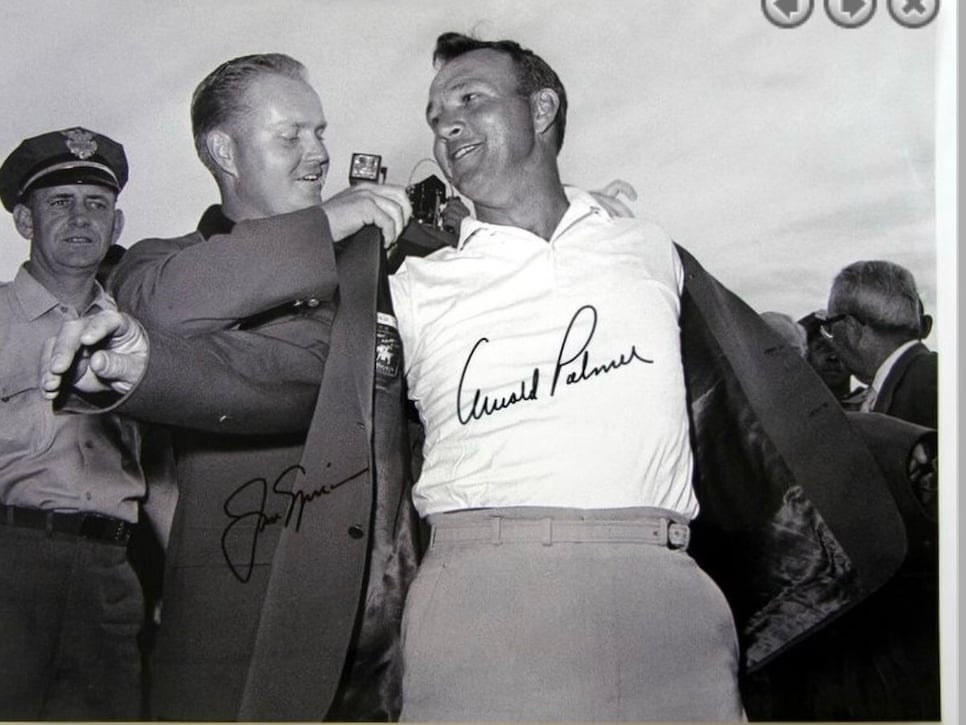

This 1964 photo of Nicklaus and Palmer was critical to authenticating the stolen jacket.

Hear “golf collectibles” and you might imagine a fusty scene of mostly older men content to marvel at even older spoons, cleeks, featheries and whatnot, but the story circulating the collecting world in 2025 is wild. It involves wiretaps, controlled transactions, trucks getting loaded Tony Soprano-style, a connoisseur with a private jet saving the day and, most importantly, a breathtaking list of treasures that went missing: the green jackets of Arnold Palmer, Ben Hogan and Gene Sarazen; a Masters trophy; tickets and programs from the first Masters in 1934; signed letters from Bobby Jones and more.

All to say, when’s the movie and who’s George Clooney going to play are two questions not normally bandied about the annual convention of the Golf Heritage Society.

Every green jacket features a handwritten label

When the Feds knocked on Globensky’s door, he owned to taking it all essentially immediately. He’s on the hook to pay back $3.7 million more, which, the impending prison sentence aside, will be difficult given he makes less than $100,000 per year at his current job and his employment prospects as a felon don’t stand to improve greatly. Calculating the restitution figure was rather philosophical, as what loss did Augusta National incur when unsold items marked to be destroyed were stolen? And then, what value do we assign artifacts that are in essence priceless, except when occasionally subjected to the bidding contests of very wealthy collectors? After much paperwork and consternation, the arrived answer of $5.3 million was straightforward—the total amount Globensky made from his illegal sales.

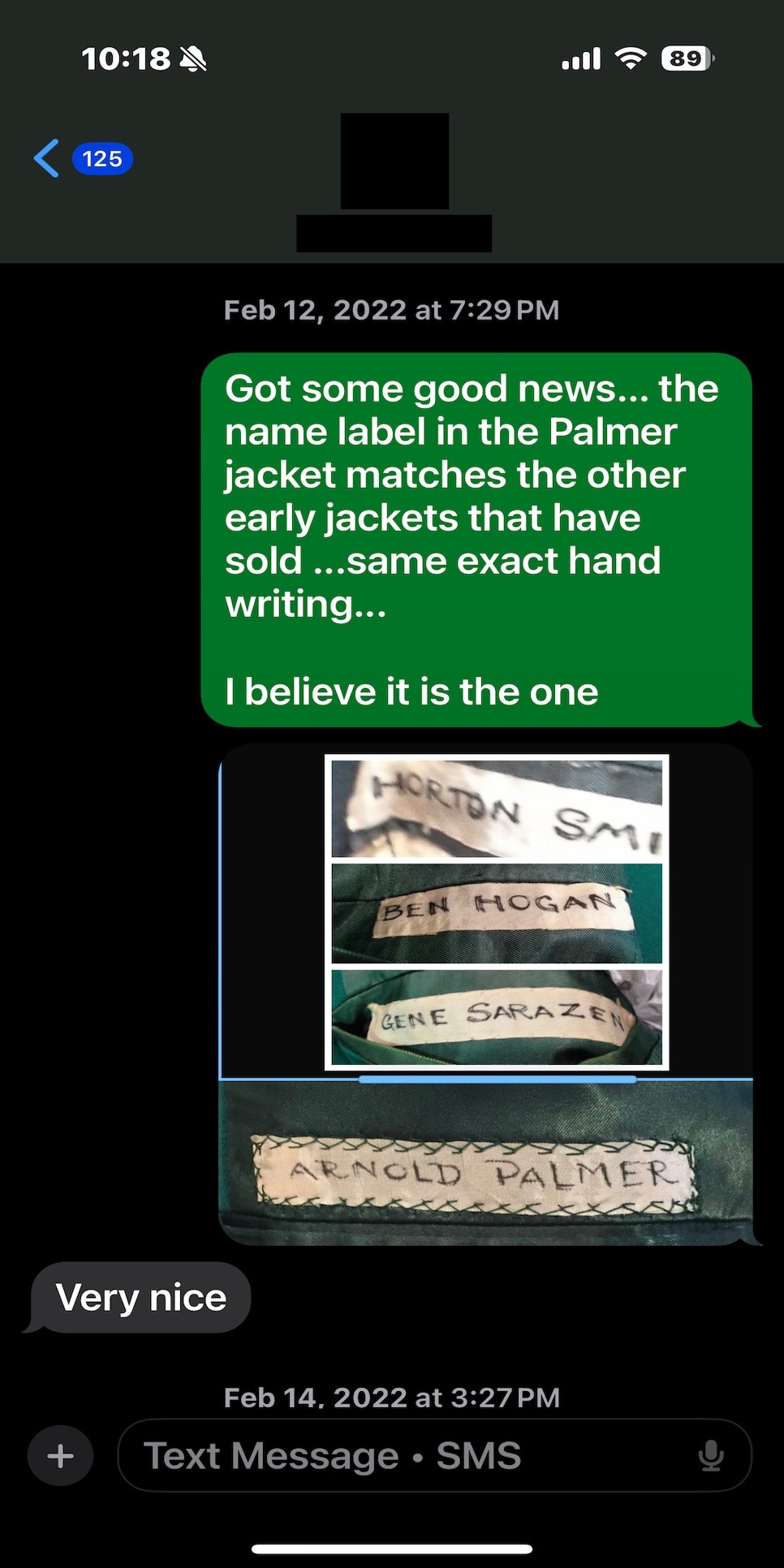

Palmer’s jacket in the home of the reputable Chicago collector who thought its provenance was legitimate.

One way to complicate even that answer is to ask: Why after years of cooperation with the FBI has nobody else been arrested? The people who knowingly bought stolen goods from Globensky could be liable to share that debt or more, and they surely profited more than $5.3 million. We can assume this because—lovers of golf history, read this sitting down—Globensky received $5 million for the truckloads of relatively low-value merchandise, but just $300,000 for all the memorabilia—the three green jackets, the trophy, the tickets, the letters and other items. In 2013, Horton Smith’s family sold his jacket at public auction for $682,000. While the inaugural champion from 1934 and again in 1936 is a figure of great significance, Horton Smith is no Arnold Palmer.

Originally, Globensky applied to Augusta National to wait tables, but the job opening was in the warehouse. When he started work, the main warehouse was at the corner of Washington and Eisenhower, and there were two other storage spaces on club grounds beneath the shops. For half the year, the warehouse had a small crew of 10 or 12 people, and the other half it ramped up with additional workers, including many PGA professionals from northern sections whose pro shops were closed or quiet during the winter season. “It was a neat little game we played receiving and moving stuff where we could not run out of space,” Globensky told me in an interview with his lawyer, Thomas Church, present. “Like, you can’t receive hats until February because there’s just so many of them.” Globensky remembers the club receiving about 30 containers from China every November, and then another 75 domestic truckloads closer to the tournament. “Some paths were just wide enough to walk down to take inventory and others just wide enough to drive a forklift, within inches.”

What loss did Augusta National incur when unsold items marked to be destroyed were stolen?

A recent estimate of the total gross merchandise sales during Masters week is $70 million, or about $1 million per hour—incredible demand that is strengthened by the fact the items, from windbreakers to garden gnomes to scotch tumblers to almost anything imaginable, can be purchased only on-grounds during the tournament. The exception to this rule has been a smattering of unauthorized reseller websites, the leader of which is MMO Golf, formerly known as Masters Mail Order before the club forced its name change. In the early days, owner Kenley Matheny would rent a house in Augusta during Masters week for a crew of mostly college-age kids to whom he would distribute cash along with shopping lists. This enabled him to photograph and list products on his website week-of and continue to sell all year—at considerable markups, of course.

Richard Brendan Globenksy at the Masters

This was and is perfectly legal, though frustrating to Augusta National. MMO Industries is a registered business in Tampa, Fla., and a bank there, convinced of the soundness of Matheny’s business plan, would provide him workable terms on short-term cash loans. As the Masters transitioned to digital payments, so did MMO, which continued to evade detection. Who would be a suspicious shopper anyway? Anyone who’s been to the Masters has witnessed the throngs walking with laden bags having clearly spent high-three or four figures on clothes and trinkets. Many utilize the expediently managed shipping services center between the range and the first fairway.

After the 2009 Masters, Globensky, emboldened, began taking more than was “customary.” A leftover box of Bobby Jones brand shirts with a loud pattern caught his eye, and he posted a couple on eBay. An intrigued buyer messaged asking if they were authentic, and an in-person meeting ensued.

After the 2009 Masters, Globensky, emboldened, began taking more than was “customary.” A full box of Bobby Jones brand shirts with a loud pattern caught his eye

Globensky’s attorney would not confirm or deny that this buyer was Kenley Matheny, though Golf Digest has it from reliable sources. Matheny has not been charged and did not respond to Golf Digest’s request for an interview.

Horton Smith (left) shakes hands with Bobby Jones in 1934. Smith’s jacket would sell at auction for $682,000 in 2013.

“He’s smart,” Globensky said of Individual 1, as he, Matheny, is referenced in multiple case documents. In addition to business, Globensky says they quickly bonded over talking football and gambling. “He goes to The Open and buys stuff for all the fans who don’t make it over. He picked through the PGA of America headquarters [in Palm Beach Gardens, Fla.] before they moved to Frisco [Tex.]. He’s big with college merchandise.”

In time, Globensky says, he developed a feel for which items never sold out as well as “shrink rates,” or the downward variances in audit figures tolerated by his supervisors. From the warehouse, he sent photographs of items to Matheny, who responded with specific requests. Globensky would then transfer those items to storage facilities he leased in town before the Masters. Matheny would drive north from Tampa, usually in a 27-foot box truck, and together they’d load. At other times, they simply used commercial carriers such as UPS. While the volume of this scheme escalated, Globensky took night classes at Augusta State University and graduated with a degree in business administration.

Globensky claims that during renovations to the club’s vaults, items that were normally stored securely were temporarily placed openly in the warehouse—a restricted area, nevertheless. When he first came across Ben Hogan’s jacket in 2011, he thought it was a replica because the original ivory-colored buttons didn’t look quite right. (The club switched to brass buttons in 1974.) When he found a white cardboard hanging box with “AP” written on the outside, Globensky’s first thought was “Associated Press” until he opened it and discovered Arnold Palmer’s jacket, identified by the handwritten nametag on the inside with a drycleaning tag still affixed. He walked outside with the jacket, put it in the van and drove across town to his storage container. On the way, he says, the notion occurred that he was a hero of sorts for possibly saving it from accidentally going to the incinerator.

What about the tradition, core to golf but also the South, of just trusting people?

The Golf Auction, which bills itself as “USA’s Top Golf Auction Site,” is registered to the same Tampa address as MMO Industries with Kenley Matheny also listed as an owner. Basically, MMO Golf is for merchandise and The Golf Auction is for memorabilia. You’d buy a plain Masters flag at the former but a signed one at the latter. The Golf Auction paid Globensky just $5,000 for the Hogan jacket he wasn’t sure was genuine, and just $50,000 for the Palmer jacket whose authenticity seemed certain.

In 2010, Augusta National declared they owned all green jackets. That members and Masters champions had “possessory rights” to have and use a jacket but that ownership ultimately resided with the club. This would address civil suits with collectors who viewed otherwise. “They changed the rules,” says our same Chicago collector, whose first green jacket acquisition was famed auto-engineer and Augusta National member John DeLorean’s, which he bought for $8,000 at an estate sale. “The fact of the matter is, if you go back to the old champions, many of whom are still alive, they’ll all tell you the same thing: that [Augusta National] never said one word that I didn’t own the jacket or that they owned the jacket. For certain I never signed anything acknowledging that. After Bob Goalby died, one of his sons received a call from Augusta National, offering tickets and the message, ‘We hope you enjoy your father’s jackets.’ Hint: Don’t try to sell them.”

(Goalby won the Masters once, in 1968, the year of Roberto De Vicenzo’s cruel scorecard gaffe, and so the plural “jackets” refers to how multiple jackets might be assigned to an individual as girths change with age, or spills from cocktail hour and dinner are suffered.)

“It was scary as f---, you know, right away,” Cornett remembers. “Why is the FBI taking this item away?

Fearing any jacket that surfaced would be asserted as stolen by Augusta National, the Chicago collector made best guesses verifying items quietly. When he decided to buy the Hogan jacket for around $100,000 in a private sale from The Golf Auction, he accepted the rumor circulating among cohorts that at some point some lockers had been cleared out and an employee or somebody in the process “had rescued them from death row.” Kip Ingle, representing The Golf Auction, told the Chicago collector without hesitation the source was a local man named Globensky. One or two years later, Ingle approached again, this time with Palmer’s jacket. The collector called expert Bob Zafian, who had a notebook of Augusta National’s memorabilia inventory from 2005. Out of four serial numbers pertaining to Palmer jackets, none matched the number of the jacket Ingle was offering, so, feeling confident it wasn’t stolen from Augusta National, the Chicago collector purchased the Palmer jacket for low six-figures. (Ingle has not been charged and did not respond to our request for an interview).

Because of the stance Augusta National had taken toward ownership of all jackets, Ryan Carey, the owner of Golden Age Auctions (a separate auction house never involved with Globensky’s stolen items), which executed the Horton Smith sale, sympathizes with the judgment call made by the Chicago collector. However, as a business owner, Carey was flabbergasted at the decision of The Golf Auction, his competitor, to sell such a marquee item behind closed doors and at such an inexpensive price. “As an auction house, not only do you want a public sale to raise the price, you want all the publicity you can get to grow your reputation.” Carey is no rookie to legal tussles with Augusta National, which in 2017 sued him over the original name of his company, Green Jacket Auctions, as well as his right to sell certain club artifacts. During a deposition of his former partner, Palmer’s green jacket was never mentioned as a missing item. Ultimately, Carey, a passionate golfer and golf fan, acquiesced to the name change but was vindicated against all claims and received compensation for the lawsuit. (Disclosure: Golf Digest has a business relationship with Golden Age Auctions.)

We don’t know exactly when Augusta National realized certain jackets and historic items were missing. The consensus among the collectibles crowd is that during the 2010s, the club was more preoccupied with figuring out how MMO had photographs of new merchandise items live on its website the second their gates opened Monday morning. Where was the leak? Internal investigations into supply chains produced nothing. Rightly and earned, Augusta National has a reputation for conducting the greatest golf event in the world with an exactitude metaphorized by no blade of grass nor grain of sand out of place. That such theft could happen right under its nose contradicts this ideal. Yet, there must be sympathy for the enormous burden that securing and managing important collections imposes. And what about the tradition, core to golf but also the South, of just trusting people?

In 2021, after 14 years in the warehouse without a negative performance review, Globenksy was terminated for what he contends was mundane post-pandemic workforce realignment politics. For certain, it had nothing to do with why he should’ve been fired much earlier. It was later that year that Augusta National began working directly with the FBI.

The sting began when they laid the trap to smoke out the Chicago collector. Justin Cornett is a sports memorabilia collector living in Houston who has been profiled numerous times, with the profilers often comparing his discipline for investing with head over heart to what made him a successful oil and gas broker. At the end of 2021, Cornett received a call from a fellow baseball and basketball card aficionado who also happened to be very wealthy and connected. He wanted Cornett’s help finding the missing Palmer jacket.

The network of high net-worth individuals who buy expensive golf memorabilia isn’t large, so Cornett located the collector who’d bought Palmer’s jacket in short order. “U sitting down?” Cornett teased his rich friend by text. He’d photo-matched the stitched label against the famous photo of Nicklaus putting the jacket on Palmer in 1964, where in exuberance or wind or a combination of both, the jacket flares very wide to reveal the label of the maker, Hart, Schaffner & Marx, beneath the handwritten ink name in all-caps: “ARNOLD PALMER.” Prime muscular Palmer, this had to be the same jacket from his first Masters victory in 1958 being slipped on in the winner’s ceremony for The King’s fourth and final time. Cornett advised it’d be a waste of a week and about $6,000 to use a photo-resolution company to verify further. Cheekily, Cornett, a five-handicap, added: “So what are the chances we can just split the jacket 50/50 and we give it to Augusta National in exchange for membership :).”

Justin Cornett’s text with the wealthy collector who was working with the FBI before the sting.

Turning the conversation back to serious, the wealthy friend explained cost wouldn’t be an issue, but he absolutely needed the provenance of the jacket to proceed. Cornett agreed wholeheartedly, as he didn’t want any part of a nefarious sale. The Chicago collector offered the name right away: Globensky.

If Augusta National did not suspect their former warehouse worker earlier, Cornett’s text dated St. Patrick’s Day 2022 confirms this was their lucky day. The wealthy friend simply said they were “good to go.”

The problem was the collector wasn’t that motivated to sell. He was wintering in Arizona, playing golf in short sleeves, and couldn’t this just wait until May when he’d be back in Chicago? Still undecided whether he’d be the buyer or the middleman, Cornett kept peppering the sense of urgency until it was agreed that the collector’s adult son would fly from Florida on March 31 to oversee the transaction, collecting an additional $10,000 fee for his trouble. The agreed-on price was $1.65 million. While the jacket was going to Cornett, who had arranged the deal and sent a $250,000 deposit, the wealthy friend had indicated he might offer Cornett $3.65 million, although there was never intention of that or any amount changing hands.

Looking back, Cornett says he should’ve realized the wealthy friend was working with the FBI. First, there was his insistence that the jacket only travel home on a private jet. “Maybe the FBI didn’t want to risk causing a scene in a public place?” Cornett theorizes. Also, “I felt like our phone calls were being recorded because there was always a delay when we started talking about the jacket, which then went away after we stopped talking about the jacket.” Perhaps most tellingly, the day of the deal his friend showed up to the collector’s house on foot with a garment bag from Men’s Wearhouse, saying he’d parked a couple blocks away. “He’s a billionaire. He doesn’t shop at Men’s Wearhouse. So you knew that like, that was weird … Must’ve been [the FBI] dropped him off close, and he walked up with the [bag] they had given him.” The weather was sunny and balmy, so the inclination for a short walk wasn’t odd.

While he had nothing to do with the transaction, the fourth person present was Ryan Carey—who had flown from his home city of Boston to play curator for this collector before. Strangers entering the collector's home, a veritable museum, with just his son there was sensitive, and knowledgeable Carey could give a guided tour to make the experience fuller for all. Carey also liked the idea of getting facetime with two heavy-hitter collectors.

The four were in the house about an hour. Most of the time was spent discussing other memorabilia, including various sports items Cornett had brought to show his friend. The vibe was that the deal for the Palmer jacket was already done. In the final minutes of the visit, the collector’s son removed the jacket from its display in an unlocked shadow box and handed it over. “There was nothing transactional about the moment,” Carey says. “When you’re selling somebody something for $200, you want the money first, but with people of this level there’s trust.”

Carey was still at the top of the front steps when he saw five suited agents appear as if out of nowhere. They announced which governmental organization they represented and took charge on the sidewalk, the exact line of public land.

“It was scary as f---, you know, right away,” Cornett remembers. “Why is the FBI taking this item away? Then they whisper in my ear, ‘Don’t worry, Mr. Cornett, you didn’t do anything wrong.’”

“I had no idea what was going on,” Carey says. “My first thought was this somehow might be related to these guys’ other businesses?”

He opened it and discovered Arnold Palmer’s jacket, identified by the handwritten nametag on the inside with a drycleaning tag still affixed.

Everyone was separated but not detained long. The FBI already knew Cornett’s flight time and even drove him to the airport. As the men waited for their respective flights, commercial and private, the phone calls and texts started buzzing around to figure out what the heck was going on. The collector in Arizona was at a loss and having difficulty getting an answer from Kip Ingle at The Golf Auction. Unasked, the collector sent Cornett back his deposit the next day. Within hours of that welcome delivery, Cornett also received four tickets to the 2022 Masters from his wealthy friend.

The day Globensky was sentenced, Augusta National released this statement:

Augusta National Golf Club and the Masters Tournament are deeply committed to fiercely guarding from theft or misuse our intellectual property, artifacts and commercial goods associated with our brands.

We were severely disappointed to learn several years ago that a former Augusta National employee betrayed that principle, and our trust, by stealing from the Club, Tournament and even a number of legends whose accomplishments at the Masters and in the game of golf are revered by all. In short, the employee made significant personal gain with no regard for the impact his selfishness would have on the Club, players, the Tournament, and his fellow employees.

We are grateful for the service of the FBI and the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Northern District of Illinois for their hard work and dedication to bringing this matter to justice.

Meanwhile, we will continue to aggressively protect our history and trademarks while remaining diligent pursuing all our rights to recover all items that were sold, purchased or are being held by unscrupulous means.

When Globensky was first apprehended, he was led to believe that “Individual 1” was the government’s bigger target. By handing over hundreds of pages of communications, recording phone calls, regularly meeting with the FBI without his attorney and arranging an in-person transaction with Matheny in which he wore a wire, Globensky hoped he might avoid prison time entirely. In this same “controlled transaction,” Globensky recovered a 1934 Augusta National stock book Matheny had been holding. But to his and his attorney’s dismay, Matheny was not apprehended on the drive back to Florida for reasons unclear.

The next time the FBI spoke with Matheny, he had legal representation.

Globensky was sentenced to 12 months in prison. His attorney thinks he’ll serve 8.5 months and one year probation.

“While Mr. Globensky’s cooperation has not resulted in any arrests or charges of the individuals and businesses that he worked with, his efforts demonstrate an acceptance of responsibility beyond simply pleading guilty,” Church wrote in the sentencing memo and asserted that the scrutiny “Individual 1 and Business 1” are now under has likely prevented further transactions and initiated the unwinding of others. Also included in the memo were 15 letters from Globensky’s family and friends that extolled his everyman virtues (welcoming hurricane evacuees into his home, volunteering to keep score for his middle son’s baseball team) and hinted at the sentence already begun (the bullying of his children, the struggle to keep a marriage intact while living at his mother-in-law’s). The family of five has since relocated to a three-bedroom apartment, and the day he was sentenced happened to be the couple’s 15th wedding anniversary. "I deeply regret the decision that led me to this moment," Globensky told U.S. District Judge Sharon Johnson Coleman moments before her ruling.

Of course, the generous demeanor and remorse of a man who systematically stole for more than a decade and lived above his means is worth only so much. Because of his escalating greed, the game’s collective soul risks being diminished. It’s not as bad as the criminals who, also a little more than a decade ago, irrevocably melted the USGA’s U.S. Amateur trophy and Yogi Berra’s World Series rings for gold and silver, yet—and this is where we get philosophical again—if the items Globensky took never resurface and future Masters patrons are denied the emotional force of their exhibit, aren’t they just as gone?

The questions persist. Where is Gene Sarazen’s green jacket? Are other important memorabilia pieces missing? Why are MMO and The Golf Auction still in business, and why hasn’t anyone else involved been charged?

This story does not have an ending. Palmer’s green jacket is back, as is Hogan’s after its buyer promptly turned it in after being notified it was stolen. The investigation is ongoing, and with a mind toward protecting potential scenarios for recovering the still-at-large golf treasures, Golf Digest has excluded certain names and details above.

But there are two more things we can say. Augusta National now has a new and more spacious warehouse equipped with better security technology. And the upcoming annual convention for the Golf Heritage Society should be a doozy.

—Barbara Shearer contributed reporting to this story

Key Dates Across 18 Years